Essayism: Writing and the jointed lattice of thought – a short, digressive text on why I used to hate writing .

Thinking about my philosophical and conflictive relationship with writing in a fairly roundabout manner...It's nearly 2 a.m

March, Thursday, April 3. It's nearly 2 a.m. A restless night, and I thought it would be a witty idea to carve out some time for honest, heartfelt writing.

I spent hours wondering whether I should make this thought into an Instagram post or only share it with my Substack readers. I haven’t decided yet, so I am sharing the “beta” version, a reduced and shortened format of a longer and contentious conversation I want to strike up very soon. After an insightful chat with a friend, I decided to share my take on writing, but, as you know, I tend to think in a roundabout way, so it’s going to be a little bit digressive, so bear with me. I’ll divide it into 3 different sections for this first short, minuscule text: 1) divagation, 2) stimulus, and 3) ideas. Let’s see how it plays out. It's nearly 2 am, so there might be some mistakes. rsrsrs [ laughing in Portuguese internet language]. I'm a contradictory yet recovering perfectionist. Bear with me.

Divagation: writing in a roundabout way

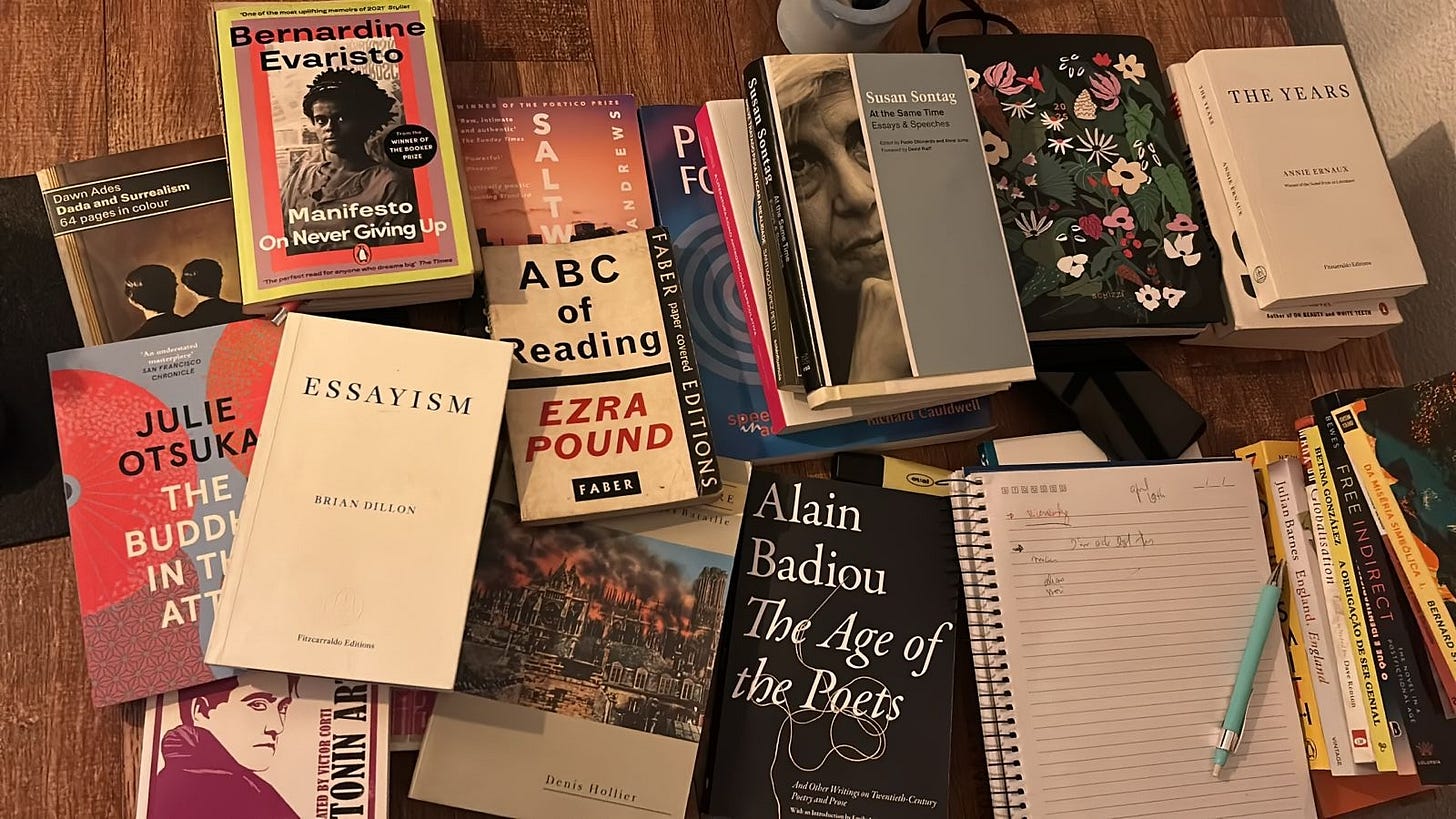

I was perusing the pages of a book that caused me to feel a hotchpotch of feelings: Essayism, by Brian Dillon. Allow me to share this quote: “writing, any sort of writing, had become a matter of distracting myself, daily.” I must confess that it made me feel a pang of jealousy, as I had always worked on my writing hoping it would become something pleasant in the long run - either for me or for my imagined reader. For this reason, I was in two minds about whether I liked it or not, as it made me reflect on how much I hated writing. I really hated writing.

Before it dawned on me that writing was excruciatingly painful, I had ruminated on the fact that working with academic writing for nearly 15 years may have had a detrimental effect on my writing process. I only resumed writing in a more pleasant way when I first heard the word “journaling,” [Thank you, Sarah ;;; credits to you] but this is a whole new ball game, and I will dissect it in an upcoming Substack.

In this line of thinking, while I acknowledge the pivotal role the university had in my life, I can’t turn a blind eye to the fact that it somewhat affected the way I was conveying my ideas. As a consequence, I’ve given thought to the act of writing and the extent to which the creative writing process may have been overshadowed by results and the unrealistic expectations learners are expected to live up to. Surprise, surprise… a pang of frustration and a sense of incompetence are some of the battle scars caused by this pernicious and stigmatised view on writing; a writing tied to validation and authorization.

Unreasonably, I was stuck in a rut and imprisoned in a violent system of unattainable expectations, which had sluggishly and silently been chipping away at my confidence both as a learner and teacher. This inherently violent process, symbiotically within a ludicrous desire to excel at writing, was subtly grinding me down - the more I deliberately made efforts to make strides in writing, the less keen on it I became. Admittedly, now that I am much more able to sense things and put everything into perspective, I realised that I was at the end of my tether, wading through - which opened a floodgate to a barrage of things that had nurtured my writing.

However, Dillon’s book turned out to be a rather motivational book, despite the fact it was nowhere near this type of material, but it was, in essence, a truly heady mix of academic and philosophical writing that prompted me to investigate language through different lenses. First and foremost, I came to understand that metaphorical writing helps us unveil dormant views of the world while navigating complex ideas and intricate language. Then, I had a dalliance with the idea that thought and language were rooted in the same system. Finally, writing was primarily akin to experimentation and leisure: it had to be pleasant but still thought-provoking.

In this context, the quality of fluid transmission through writing is subject to spurts that can paradoxically reabsorb what I had mindfully retrieved from a myriad of materials I had committed myself to exploring. From The Theatre and Its Double, by Antonin Artaud, to the ode to experimental and de-automatized poetry by the Surrealists.

Inevitably, some of the experiments of the Surrealists in poetry and the plastic arts not only served as a catalyst for freedom of creativity, but they ended up being a primer on how to borrow the voices of other artists and literary movements. Despite its unquestionably imaginary and political power, literature surpasses the mere act of connecting words - it opens up new possibilities and unearths dormant aspects of language, as it sparks curiosity and prompts people to explore language.

Above all, literature, arts, architecture, anthropology, and the humanities as a whole are full of echoes of other artistic movements. Remarkably, Surrealism, which stands for the genuine and organically true expression of the disinterested play of thought, came as a clear-cut illustration of language as a fundamental avenue for generating knowledge of the world.

On top of that, poetry, per se, is not a mere printed word on the page, but it shakes the structures of reality to open possibilities to an entirely new experience. Significantly, all attempts to encapsulate the role writing plays in our lives will not fit neatly into a rather rigid definition, but in the deflating of automatized, plastic-fabricated notions of writing to fabricate essentialized, and amorphous thoroughgoing depictions of reality, writing emerges as this vibrant and unpredictable atmosphere and ferment of new ideas generated by those who confront its policies and combat its entrenched ideas.

Unbeknownst to me, I had already undergone an irreversible process of rectifying the mistakes I had made while approaching language in my writing journey: had I solely focused on the creative process, my understanding of mistakes would both have gained different layers and had resonance for me. I started feeling less pressured to give what I thought people would expect from me, and redirected my focus to dismantling the fantasized machine that only existed in my mind.

It freed me and prompted me to respond to other stimuli, focusing on the disjunction in language between two regimes of thinking: expected and desirable images and the pure blurred ideas in the very effacement of the empirical objectivity of language. I could envision the relation of overlapping that forms the knot between repetition, inapprehension, uncertainty, and experimentation. I certainly snatched this idea from a book called The Age of Poets, by the well-known philosopher Alain Badiou, aiming to interrupt the suture of philosophy onto the poem by stepping into the unfolding of the intrinsic power of the four generic procedures of truth: science, politics, art, and love. This is done by recommitting the task of working on language.

Since then, I have started entertaining the idea of how words may dwell where thought is produced, but also serve as a way of extending our sense of what a human life can be. This is a novel idea I stumbled upon while reading The Conscience of Words, by Susan Sontag.

She waxes lyrical about the loosely interlaced perceptions between language and form: texts are made of ideas, and ideas are made of forms. Implicitly or tacitly, nobody cultivates an idea growing in the head until the form flourishes. In this vein, complexity operates within the boundaries most people want to break, but it would preemptively choke off the freedom of what texts can be: a whirlwind of ideas seeking inventiveness and an anarchic format.

Instead of writing as a materialization of our thoughts and intangible blurred images, what language can do in texts is the opposite: it can go into the jointed lattice of thought [Oh, my days, I love this idea, I must confess], but also into the concrete, singular life of our ideas: the conflicted relationship between writing and labour is patently true; but the entrenched view that writing is, by nature, a long-standing convention that comes at the cost of practice is, by a long chalk, a complete fallacy.

As a matter of fact, writing comes at the cost of waging a battle against the dominant style that tilts toward the figurative, the concrete, the objective, and the monochromatic world of plastic perfection. In the end, penning our ideas is nothing but a way of seeing words as concepts that interrogate our propensity for perfection, reproduction, and plasticity in a world where social and cultural rights, like reading and writing, are looked down upon in the name of productivity and results.

Stimulus for writing

Reading is the backbone of writing, but conversations and chats with friends are the foundation stone of writing. The more you share and engage in meaningful conversations with your teachers, tutors, and peers, the more likely you are to have an outburst of creativity. I personally love dissecting a topic with my teacher or a friend before taking a deep dive into writing. Not only does it help me gain more perspective and have a more polycentric approach to the topic, but it strikes a chord with my firm belief that writing is primarily a collective act. Writing only happens when shared.

Varying the reading sources and your font of inspirations is key to this process. It’s paramount that we become better able to navigate a whirlwind of ideas from different contexts - from pop culture to politics. I like reading about a wide range of topics, ranging from politics to architecture: I have dallied with the idea of learning more about coffee and the art of being a barista. It has furnished me with concepts and decentralized views of the world. In this sense, words are not deemed an amalgamation of random patterns and combinations, they are, indeed, complex and interlayered concepts embedded in an intricate network of ideas, references, and discourses.

Last but not least, write, write and write. Don’t think twice. Be kind to yourself, and avoid AI tools. It’d be nice to have a teacher to assist you in this process, which may come in handy for allying the fears of writing and become more empathetic about your own process.

Once we embark on a journey in which we allow ourselves to savour every bit of it, even its peaks and valleys, chances are that we become better able to let our minds wander and create room for our fears and mistakes to metamorphose into experimentation. This is the language experience at its finest: a process that epitomizes the ebb and flow of human nature.

Ideas

Start a journal. Write about your feelings and sensations toward the world. Write about something that triggers you. Write about something that drains you. Write about social and political issues that hit where you live. Write about your writing process. Write about your lessons. Write about your journey as a learner. Write about your journey as a teacher. Write about contentious topics. Write about the abstract. Write about sociology, philosophy, linguistics, architecture, poetry. Write about your vulnerabilities. Write about your deepest feelings. Write about how you abhor productivity. Write about your thoughts on capitalism and social disparities. Write about anything that comes to mind. Write about your favorite person in the world. Write about language. Write about writing. Write

Writing process: what a mess, I know.